Editor’s note: Originally published December 12, 2017.

Some people are born with a silver spoon in their mouth. Everything for them is easy and smooth.

You’re not one of those people.

The odds are against you from the beginning.

Your name is Carl Gipson.

You’re born in 1924 in the small town of Tarry, Arkansas.

It can barely be called a town. It's more like a cluster of farms south of Little Rock.

Your grandfather was born a slave. You have dark skin. You play only with other dark-skinned boys. You drink out of "colored" drinking fountains.

You grow up in the Great Depression. Your mother stitches clothes from burlap sacks.

You go to an all-black high school in Little Rock. The girls are kept separate from the boys except at lunchtime. One day you’re in the lunch line with a girl named Jodie. She asks you if you’ll buy her lunch. Well, sure. Anything for a nice girl.

A romance is born. You marry Jodie after high school. You’re married to Jodie for the next 65 years.

This famous photo is from the federally-mandated integration of Central High School in Little Rock, 1957. Carl Gipson lived a few minutes from Central High in the 1930s, but was forced to walk across town to attend an all-black high school.

You and Jodie try to farm in Arkansas. After a year of working the soil, you make only $140.

World War II is on. You and Jodie move out to shipyards in California. You work there with 7,000 other African Americans. First you live in a trailer then you live in segregated housing projects.

One day at the shipyards an FBI agent pulls you aside.

“You’re Carl Gipson?”

Sure.

“Where’s your draft card?”

Back in Arkansas, you reply.

“That’s what we thought.”

You don’t go home that night. The FBI agent sends you straight to Washington state. In Oak Harbor you’re enlisted in the navy. As punishment for being an accidental draft dodger, you cook and clean house for the base commander.

You are unfailingly polite and kind. Your demeanor and work ethic win you rapport.

Carl and Jodie Gipson.

Jodie follows you to Washington. The war ends.

You don’t have enough money to buy a house. No one will rent to you in Mount Vernon or Anacortes. It’s because of the color of your skin.

You rent a place in the Everett projects. You meet a man named Sevenich who runs a car dealership downtown. You start working at the dealership, pulling blackberry vines off the building, delivering cars. You’re unfailingly polite and kind. Sevenich notices this.

One morning the foreman quits. Sevenich promotes you to foreman.

The next day your crew at the dealership clocks in and then they leave. They don’t want to work for a black man.

Sevenich is mad. He threatens to fire everyone. The crew comes back reluctantly, begrudgingly.

This doesn’t kill your kindness. You treat everyone with respect. You have to be double nice in a society that sees you only for your skin color.

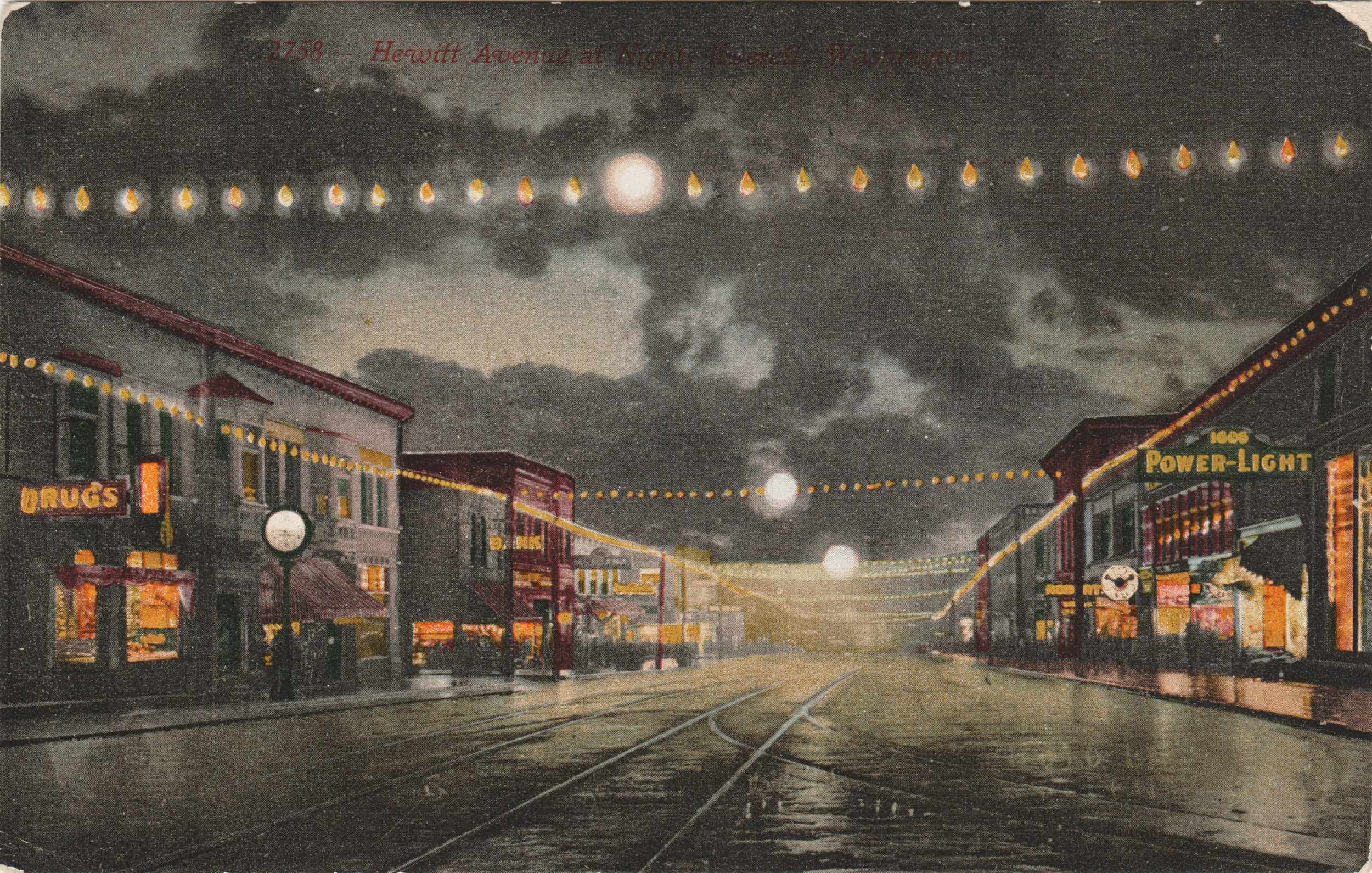

Everett in the 1940s. When the Gipsons moved here in the 40s there were five other black families in the city.

You save enough money and buy a house in a white neighborhood, on the corner of 19th and Hoyt.

Your new neighbors aren't happy. They threaten to burn your house down. You ignore them and move in anyway. Eventually they mellow out.

You open a car service station.

You’re appointed as president of the Everett chapter of the NAACP.

_

One day the mayor stops by your service station. He mentions that several council members are running unopposed. He says you should run for the Everett city council.

You have three sons and a mortgage, little money to run a political campaign. The ladies from your church throw a bake sale to raise campaign funds.

You attend political debates and rallies in overalls, carrying a lunch pail. The message you send is clear: you’re the same man clocking into work at 8 AM as you are on the political stage at 6 PM.

You win the election in a landslide.

You spend 24 years on the Everett city council, sometimes as president of the council.

Your philosophy is simple: listen to voters. Truly listen. If you can offer help, you offer it. You help the city with a swimming pool and the purchase of aid cars.

The way isn't easy or smooth. You have lots of friends, but some people still oppose you. The Elks Club rejects your membership, votes you down.

Again, the color of your skin.

You win people over slowly with charm and hard work. You shouldn’t have to win them over, but you do.

Late in your career you travel to Washington D.C. to speak in support of a navy complex being built in Everett. On one of your trips to the capital you sit and talk with First Lady Hillary Clinton.

You retire in 1995. In your farewell address you say that your guiding principles have been the ten commandments. You quote the golden rule.

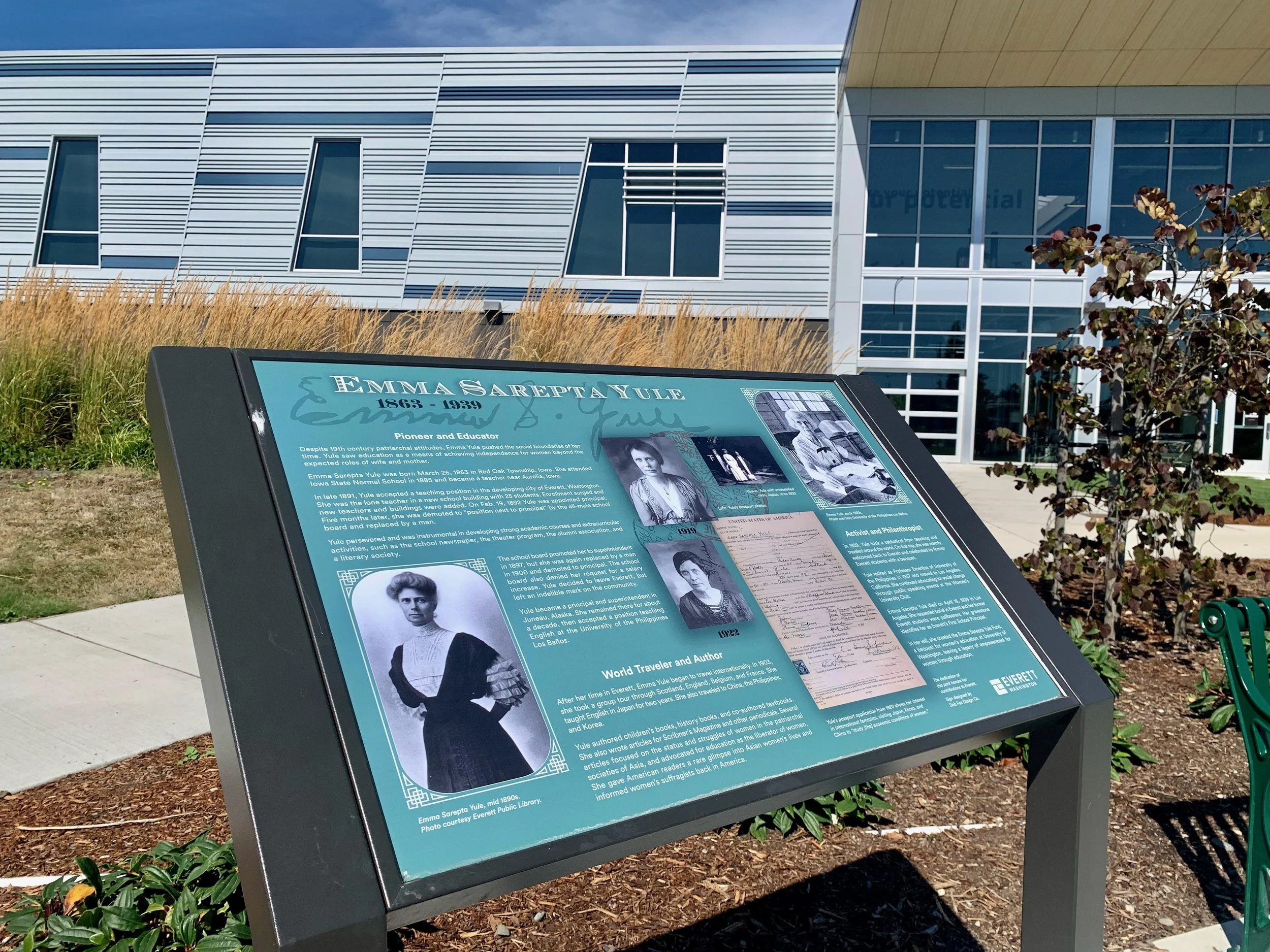

Fourteen years later they name the city’s senior center after you.

You are well loved by the community.

You sit in your home in retirement and think back on your life. Once a week you eat lunch at the senior center that bears your name.

No, life has never handed anything to you on a silver spoon. You were denied housing, equal educational opportunities, had to hustle through a grinding Depression. You’ve been kind and worked hard to impress those who gave you grief for no good reason.

People will remember that. They will remember the kindness you repaid for evil.

They will remember you fondly, Carl Gipson.

Carl Gipson passed away on October 9, 2019 in Everett. He was 95.

The Carl Gipson Center is a membership-based community. The center serves seniors (age 50+), veterans, individuals with disabilities, underserved communities, immigrants, youth, and families.

Seniors are welcome during all operating hours. Members under 50 are welcome to participate from 2:00-5:30 PM, Monday through Thursday, and on Saturdays.

CARL GIPSON CENTER

3025 Lombard Avenue

Everett, WA 98201

(425) 257-7082

Richard Porter is a writer for Live in Everett.